“You can find me on Spotify, where I’ve published my tracks,” said the singer. She had a stunning groove in her voice that echoed around the buildings. The streets of London were bustling with people. Only, the sounds coming from the pink-haired girl’s guitar felt refreshingly sane. She managed to make people stop and feel something for a while, before returning to work and worries, or dreads and dreams. I had placed a £10 bill in her hat and asked if she had any CDs available.

I’m old school, that’s what we did back in the days before streaming services made it easy to distribute music. She smiled and pointed at a little cardboard sign next to the hat with the coins. It had her name, a URL, and a QR code. “Oh” I said, “great, Amy Z. I’ll look you up there”. “Don’t forget to like and share with your friends,” she nodded in excitement. – “Sure.”

This was four years ago. I’ve sometimes wondered what became of this passionate musician. I was kind of waiting for her to become famous. But that didn’t happen.

Instead, I ran into her at my nephew’s school. There she was, giving guitar lessons to a first-grader. “It pays the bills,” she explained. “My own music doesn’t!”

Besides, some of her work had been stolen and reused by someone with better connections. “The industry is viciously competitive, you never know how much you get paid and when. And it’s really tough to protect ownership rights.” And then she raised her voice to sing “I need dollar, dollar, dollar is what I need” (that wonderful Aloe Blacc song). She sings for the soul and teaches for the money – for now.

The tragedy of the music industry

There must be thousands if not millions of aspiring musicians feeling disillusioned with turning their passion into a profession. Music – even though perceived as art – is big business. Not only that, the business model is completely outdated and unbalanced.

Even successful performers find themselves in similar positions as AmyZ.: “Music is over-convoluted right now, there are so many sectors in the entertainment business.” says the American songwriter, producer, and entrepreneur Akon ”The artist is last to get paid, he’s the brokest one outa everybody”.

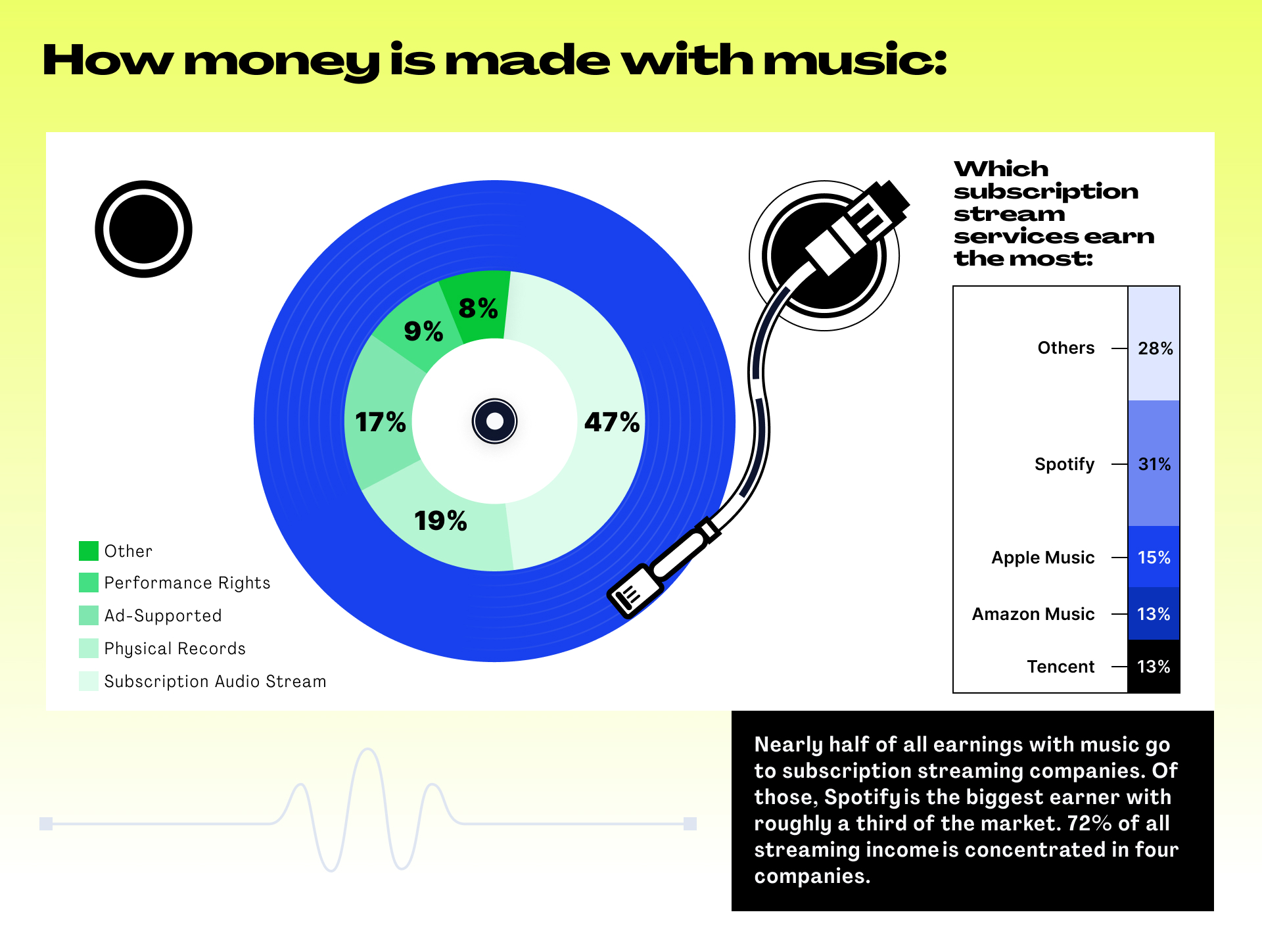

If musicians can’t make a living, where does all the money go? According to the IFPI in 2021 the annual revenue of the recorded music industry reached $26 billion globally. A whopping 68% of earnings go to three major recording companies: Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment, and Warner Music Group.

But that’s not even who Akon was talking about. With everybody, he meant producers, technicians, managers, agents, attorneys, studios, and other middlemen who cut their share of the profit. Every piece of music goes through a long, intricate supply chain that starts with the musician. The payment travels backward through the chain. After every stakeholder along the way cuts their share, there isn’t much left for the artist.

And there’s another troubling issue. Musicians don’t own their music. As soon as they sign a contract with a recording company, they give up control.

Rock star Prince told the media at the height of his career: “ …I was recording the albums myself in my own studio. And so, the way I looked at it, I owned the work because I paid for it and I did all the work. […]. That said, the companies felt otherwise and they would always hold this contract up and said, well you signed it!.”

He tried to work out more reasonable conditions, arguing. “…it shouldn’t be a situation where they own the work – we’re talking about international copyright. If they are indeed a delivery service then that’s fine. but even FedEx doesn’t say they own the thing they ship.”

The trouble with the contracts

A typical musician’s contract grants the artist a percentage of the profit from their music – the royalties. The rates and conditions are determined by the label and based on obscure calculations. Starting musicians often don’t understand the implications of the contracts they sign. Later, they have trouble proving ownership rights or the right to get paid.

“They’ve created this strange convoluted system, that you have to be a lawyer or a mathematician to understand.” sais Brandon Boyd from Incubus and adds “We had to sue our label to get paid.” Chester Bennington from Linkin Park puts it in simple words: “When you’re saying yes to one thing, you’re actually saying yes to 45 other things, that they’re not talking about.

The royalties percentage may look good in the contract, but one thing musicians overlook are deductions, such as part of the promotion and recording costs. Some of them sound reasonable, but if the artist doesn’t pay attention, completely irrelevant items, such as packaging and shipping-related deductions may incur on digital downloads.

“There’s a worse one” says Serj Tankian from System of the Down “they used to have damage fees for digital downloads.” What does that even mean?

More hype than hope from streaming sites

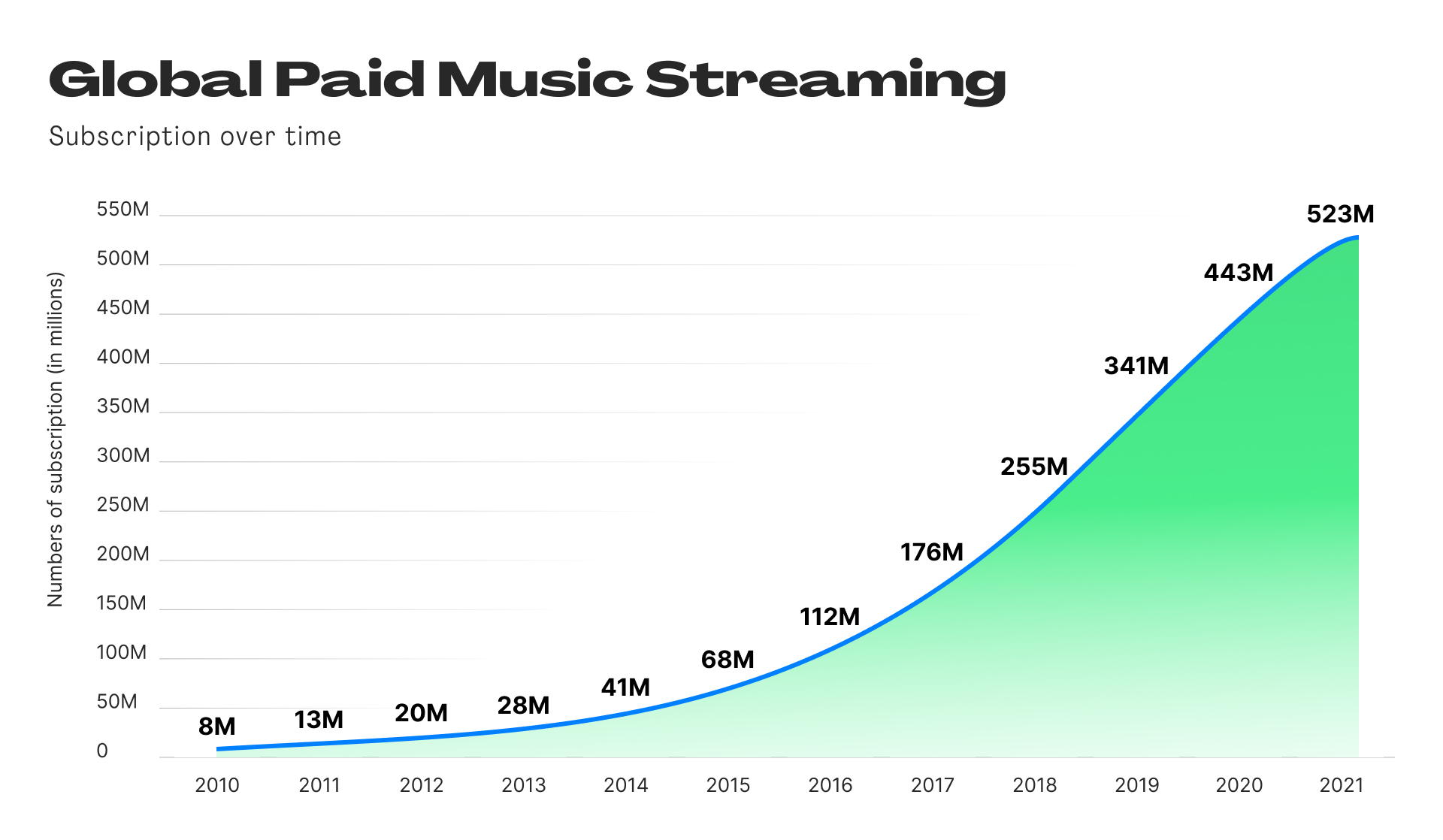

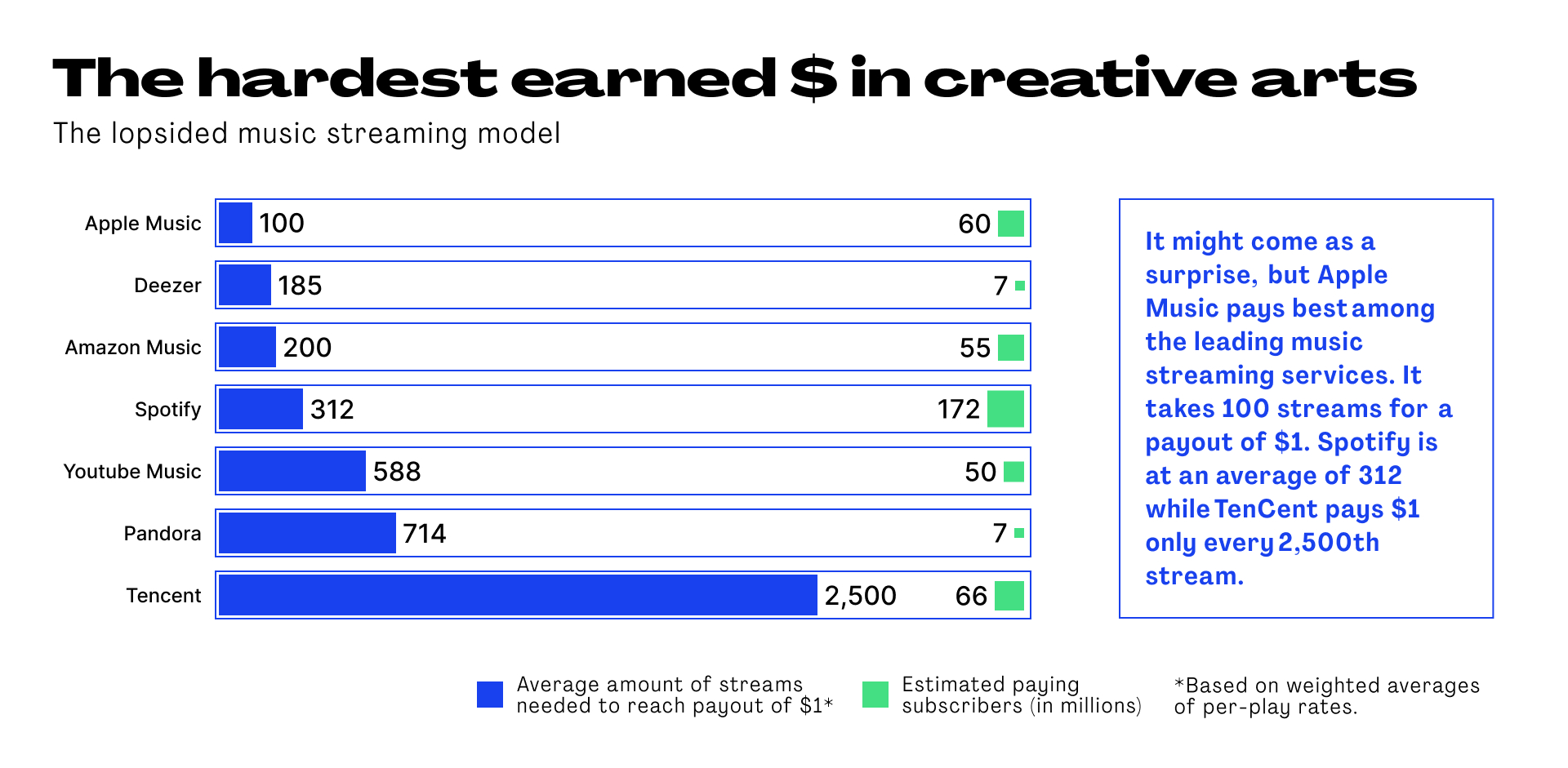

When Apple launched ITunes in 2001, musicians hoped for some redemption. Digitalizing music distribution would break the power of the big labels. Apple’s digital music store was followed by streaming sites like YouTube, Spotify, Deezer, and Tidal. On streaming platforms, musicians can upload and publish music without depending on a recording company and their tricky contracts – or so they thought. Artists get paid per streaming, regardless of whether the listener has a paid subscription or not.

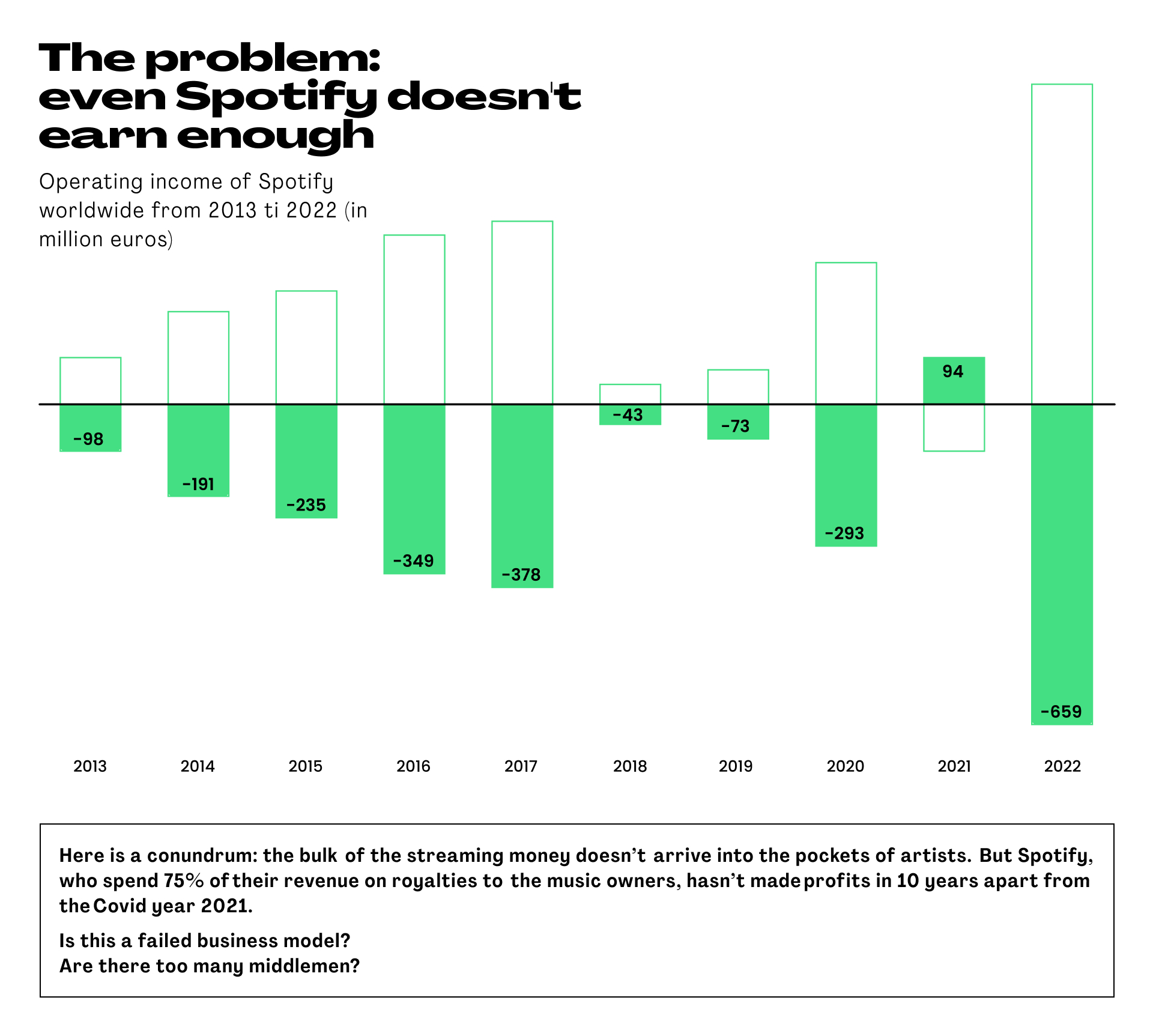

Indeed, the new method has caused a shift in the music industry. In 2021, streaming services gobbled up 65% of the industry’s revenue.

Currently, there are over 520 million subscribers worldwide. Spotify has the highest number of subscribers, followed by Apple Music, Amazon Music, and Tencent Music.

Who benefits from the change?

In theory, this sounds like a good deal for musicians. In reality, not much has changed for them. Apple and Spotify didn’t have the artist’s benefit in mind when they launched. They wanted to provide convenience for the consumer – those who bring in the money. So, the way we consume music has dramatically changed, but the position of the musician remains much the same.

No news for musicians

Established musicians are bound by contract to the labels and streaming sites are an added link in the supply chain.

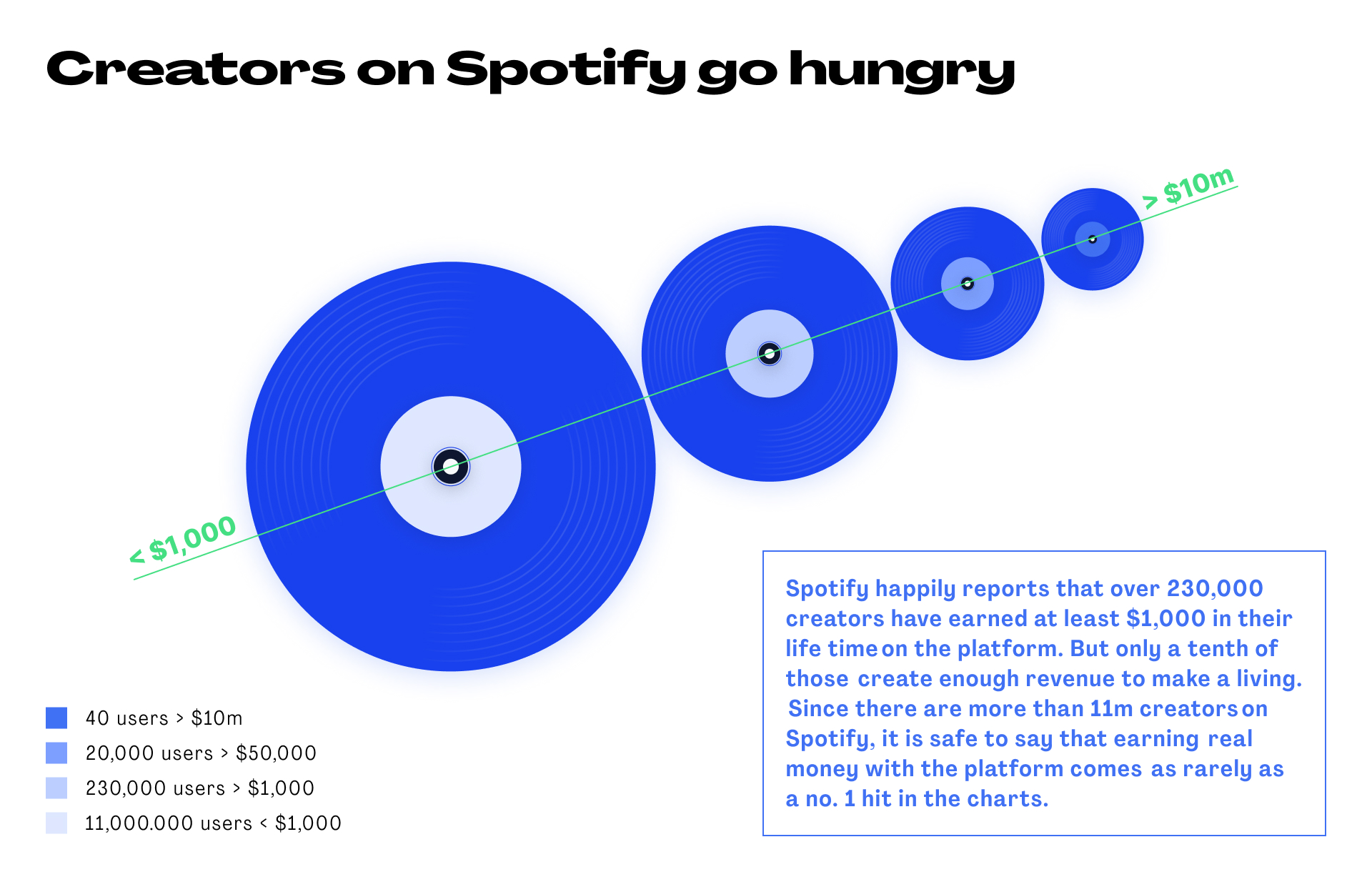

For aspiring artists, like Amy Z. giant internet companies replace record labels. The musician invests the work and money to produce and record music. Then they pay to publish it on the streaming site and hope to generate enough streams to cover their expenses and create an income. With about 10 million songs uploaded each day, the competition is fierce. The average artist earns $1.000 on Spotify per year.

Many musicians turn to alternative ways of making money, like producing beats and background music, doing affiliate marketing, and giving instrumental lessons.

Copyright infringement is an even harder nut to crack. In 2017 about 35% of internet users downloaded music without permission. Since then, new ways of securing music files have evolved. However, the legal situation is complex and there is no technology to trace a piece of music back to its original creator and owner. Actually, there is, but streaming sites aren’t using it (yet).

The times, they are a-changing

So, what’s the solution to an industry stubbornly set in its mischievous ways? One way to approach the need for change is through technology. New streaming sites such as Muzikie take on the challenge and use the unique capabilities of blockchain technology to provide a fair and supportive environment for musicians. This app is by far not the only one.

The 2017 Gartner Hype Cycle Report states that “for the purposes of disintermediation in the music industry, it [blockchain] shows great immediate potential.” The reason is that it solves the music industry’s two main problems:

- The lack of access to transactional information

- The inefficiencies associated with royalty payments

Blockchain music apps – putting the musician first

The distributed ledger technology eliminates copyright disputes on songs, albums, and playlists because records are immutable. Embedded smart contracts ensure creators and other stakeholders in the music value chain – songwriters, musicians, producers – get paid the correct amount on time.

According to Imogen Heap, a Grammy-winning recorded artist and blockchain supporter, “One of the biggest problems in the industry right now is that there’s no verified global registry of music creatives and their works. Attempts to build one have failed to the tune of millions of dollars over the years […]. This has become a real issue, as evidenced by the $150 million class action lawsuit that Spotify is currently wrestling with”.

Using a blockchain, such as Lisk, the one Muzikie builds on, this issue could be eliminated. Musical records would always be attributed to the original creator and owner. All relevant data surrounding a music track is stored in a dynamic music file. This includes data required to identify ownership and payment rights. The entire process is simplified and rooted in a single version of truth.

What’s in it for the fans?

We haven’t mentioned the audience yet. Ultimately they are the ones who pay and they expect value in return. The truth is, most fans don’t know their stars only receive a tiny fraction of the money and if they knew, they wouldn’t be happy about it. Blockchain-enabled music sites allow fans to support their idols directly and will reshape the relationship between the musician and the audience.

The artist can raise funds for projects directly from fans using peer-to-peer transactions. In return, performers can offer their sponsors tickets, merchandise, or even a share of future income. His would give fans a new sense of connection to their idols.

Blockchain music app with a vision

Blockchain could bring the much-needed rectification of the music industry.

Muzikie founder Ali Haghighatkhah wants to bring transparency and value to the industry. He is a software developer with a passion for music in general and oriental music in particular. His vision is to offer niche music genres a better chance to be heard and also allow mainstream artists to earn a fair income. In the future, he envisions decentralized labels that redefine the connection with the artist.